August 2024

The effects of exercise on longevity are uncertain (historical examples)

By Ilia Stambler

Exercise is generally considered beneficial for promoting healthy longevity. It is perhaps one of the very few means available to us today to influence our health and longevity. But how much exercise is good for healthy longevity? (What are the dosages)? Which kinds, combinations and time schedules of exercise are good? (What are the regimens?) What dosages and regimens of exercise promote healthy longevity for which people? (What is the personalization?) In particular, what exercise dosages and regimens promote healthy longevity in older people, taking into account their declining functional capacity? “The devil is in the details.”

These still appear to be largely open questions, emphasizing the need for thoughtful research. The openness of these questions is exemplified by historical examples of longevity studies, often showing discrepancies and contradictions in the effects of exercise on longevity for different groups. Some of the examples are listed below, demonstrating the virtual impossibility to speak of longevity benefits of “exercise generally” and emphasizing the need for personalization, and careful and thoughtful study.

One of the earliest examples of such discrepancies can be found, in the beginning of the 20th century, in the works by the American longevity researcher James Rollin Slonaker (1866-1954) considering the relation of exercise to longevity in rats. In Slonaker’s experiment, the animals were subjected to different levels of physical exertion. It was found that, in the exercising group, the more exercise the animals had, the longer they lived. However, the animals that did not exercise at all, but had “usual mobility,” lived longer than those who exercised. The question then arose whether exercise per se is beneficial, or rather which amounts of exercise are beneficial. May physical work shorten life? What would be an exact threshold at which physical work becomes exhaustive, and at which the beneficial effects of stimulation and training are superseded by fatigue and wear and tear?

(Slonaker, J. R., “The normal activity of the albino rat from birth to natural death, its rate of growth, and duration of life,” Journal of Animal Behavior, 2, 20-42, 1912.)

The confusion regarding the role of physical activity for longevity, introduced by Slonaker, has continued in longevity science literature. Generally, physical exercise has been regarded as beneficial for longevity. Yet, there have been conflicting findings.

Thus, it was found that athletes live longer than normal insured men, but shorter than “physically underdeveloped” people. (Louis I. Dublin, “Longevity of college athletes,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine, 157, 229-238, 1928.)

It was also found that athletes live longer in general. (Martti J. Karvonen, “Endurance sports, longevity and health,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 301, 653-655, 1977.)

And it was also found that athletes live shorter in general. (Peter V. Karpovich, “Longevity and athletics,” Research Quarterly, 12, 451-455, 1941.)

And there were also found no significant differences. (Henry J. Montoye, et al., The Longevity and Morbidity of College Athletes, Indianapolis, 1957.)

The results also varied widely depending on the type of sports, level of athleticism, period of practice, and many other factors. (Anthony P. Polednak (Ed.), The Longevity of Athletes, Charles C. Thomas, Springfield IL, 1979.)

It was also shown that “blue-collar,” physically active workers live shorter than sedentary “white-collar” workers. But this was explained by the assumption that the “white-collar” workers were able to exercise regularly, in a protected environment, and with sufficient rest. (Charles L. Rose and Michel L. Cohen, “Relative importance of physical activity for longevity,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 301, 671-702, 1977.)

(These works are reviewed in William G. Bailey, Human Longevity from Antiquity to the Modern Lab, Greenwood Press, Westport CN, 1987, “Athleticism and Exercise,” pp. 98-104.)

The general uncertainty about the role of exercise for influencing human longevity, aging and aging-related diseases was well expressed by one of the founders of American institutional gerontology (one of the founders of the US National Institute on Aging) – Nathan Shock, who wrote:

“In no case did the athlete group have significantly different longevity from a random group of college men. However, honor men or intellectuals had a two-year longevity advantage over athletes and the general group of nonathletes. …

In view of the lack of clear evidence of the effect of exercise on the incidence of coronary artery disease, the Task Force on Arteriosclerosis of the National Heart and Lung Institute (1972) concluded that there was not enough evidence to warrant a trial of exercise in the primary prevention of coronary heart diseases. …

aging in the total animal may be more than the summation of changes that take place at the cellular, tissue or organ level. Life of the total animal requires the integrated activity of all of the organ systems of the body to meet the stresses of living… with advancing age, regulatory mechanisms are less effective. Much work remains to be done to identify the mechanisms which are critical in explaining the reduced effectiveness of adaptation, which is associated with aging in the total animal.”

(Nathan Wetherill Shock [1906-1989, National Institute on Aging, NIH, and the Baltimore City Hospitals]. System Integration. In: Finch CE, Hayflick L (eds) Handbook of the biology of aging. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, 1977, pp 639–665)

The uncertainty has continued. One of the more recent examples in confusing findings is Howard Friedman and Leslie Martin’s The Longevity Project. Surprising Discoveries for Health and Long Life from the Landmark Eight-Decade Study, Hudson Streen Press, Penguin Group, NY, March 2011.

Based on the analysis of a group of 1500 subjects, Friedman and Martin basically suggested that many factors popularly associated with decreased longevity – such as lack of exercise, demanding careers, anxiety, risk-taking, lack of religion, being unmarried, unsociability, pessimism, stress-producing Type A behavior, various dietary taboos – should be taken with a large grain of salt. For example, the more cheerful and relaxed people tended to live shorter than “prudent and persistent” individuals (p. 9). The book also suggests that strenuous exercise does not necessarily lead to greater longevity (pp. 105-106).

Many more such examples of uncertainty can be quoted, altogether emphasizing the need not just for “further research”, but mainly for “further understanding”.

(See also: Ilia Stambler. A History of Life-Extensionism in the Twentieth Century, Longevity History, 2014 http://www.longevityhistory.com/ )

https://www.longevityhistory.com/read-the-book-%20online/#_edn673

Theories of Mortality

Theories of Mortality

http://www.longevityhistory.com/theories-of-mortality/

Mildvan AS, Strehler BL (1960) A critique of theories of mortality.

In: Strehler BL, Ebert JD, Glass HB, Shock NW (eds) The biology of aging: a symposium held at Gatlinburg, Tennessee, May 1–3, 1957, under the sponsorship of the American Institute of Biological Sciences and with support of the National Science Foundation. Waverly Press, Baltimore, pp 216–235

https://archive.org/details/biologyofagingsy0000stre/page/n9/mode/2up

Summarized in: Stambler I. Health and Immortality. In: Explaining Health Across the Sciences. Springer Nature, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52663-4_26

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343939936_Health_and_Immortality

And “History of Life-extensionism in the 20th century”

http://www.longevityhistory.com/read-the-book-online/#_edn1019

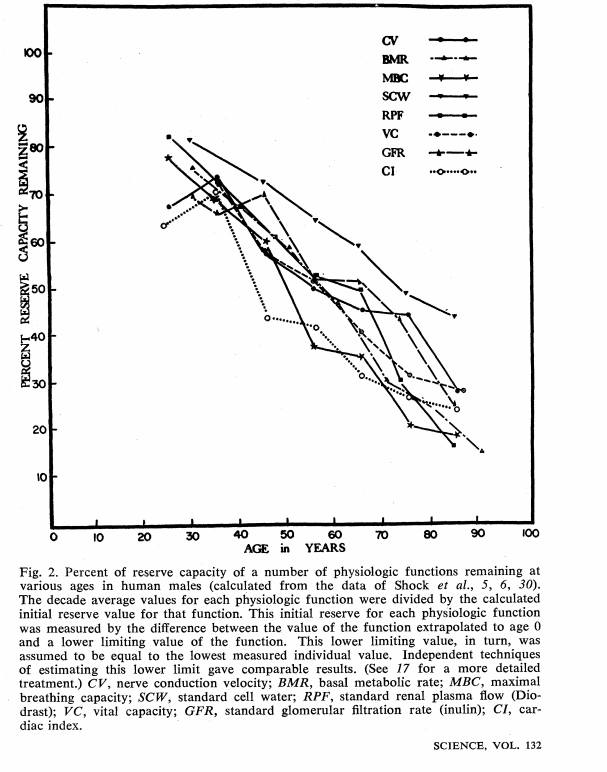

“The theories of mortality developed in the 1950s built on much earlier concepts, such as Benjamin Gompertz’s law of an exponential increase in mortality rate with age, posited in 1825, or Karl Pearson’s population mortality statistics of 1900. Yet, they were more elaborate, quantitatively relating the rate of (molecular and cellular) damage and loss to the rate of mortality. Several theories of mortality were formulated between 1952 and 1960. Thus, according to the theory of Elaine Brody and Gioacchino Failla, the “mortality rate is inversely proportional to the vitality.” In the theory proposed by Henry Simms and Hardin Jones, death was attributed to “autocatalytic accumulation of damage and disease,” where “the lessening of vitality [is regarded] as the accumulation of damage” and “the rate at which damage is incurred is proportional to the damage that has already been acquired in the past.” George Sacher’s theory stated that “death occurs when a displacement of the physiologic state extends below a certain limiting value” (Mildvan and Strehler 1960).

Yet, perhaps the most developed and publicized theory of mortality was the theory proposed by Bernard Strehler and Albert Mildvan or “the Strehler-Mildvan theory” (Strehler and Mildvan 1960). It claimed that “the rate of death is assumed to be proportional to the frequency of stresses which surpass the ability of a subsystem to restore initial conditions” (Mildvan and Strehler 1960). The theory was based on the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (originally formulated for the kinetic theory of gases in the 1860s), where the linear decline of function of particular organs in time was supposed to eventually lead to an exponential increase of risk for systemic failure of homeostasis of multiple organ systems and hence an exponential increase of mortality rate. The loss of organ function or “organ functional reserve” was potentially attributable to progressive loss of functioning organ and tissue units, such as cells, or gradual impairment in the functional capacities of individual cells (Mildvan and Strehler 1960). This model formed the theoretical basis for the “compression of morbidity” concept.”

See also: Strehler BL, Mildvan AS (1960) General theory of mortality and aging. Science 132:14–21 https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.132.3418.14

Chronographic Aging Project

By Alexey Olovnikov, PhD

[Published with permission of Dr. Olovnikov in search of support for his work and cooperation]

The essence of the chronographic aging theory, the possibility of its verification and consequences

The chronographic theory of aging (Olovnikov A.M. Chronographic theory of development, aging, and origin of cancer: Role of chronomeres and printomeres. Curr Aging Sci. 2015; 8 (1): 76-88) is based on the assumption of a consistent loss by brain’s neurons of their special extra-chromosomal DNA amplificates. They are copies of some regulatory sites of chromosomal DNA. Chromosomal originals of these copies remain virtually intact until the end of the organism’s life. Gradually losing these amplificates from neurons, a body, owing to this process, evaluates the course of endogenous time throughout life. Amplificates in neurons of a brain are designated as chronomeres. Similar amplificates are also present in other, non-neuronal cells, where they are referred to as printomeres. All these amplificates are the double-stranded DNA molecules. They are relatively small perichromosomal copies of their chromosomal originals. The length of chronomeres may be from a few hundred to thousands of nucleotides. Different chronomeres have distinct sequences depending on the specificity of those neurons in which they are located. Each chronomere is aligned “side by side” with its chromosomal original, that is next to it, though extrachromosomally. In other words, each chronomere is represented by an independent separate DNA molecule. Chronomere is fixed on a body of its chromosome like a fish-sticking on shark – in the sense that chronomere uses the chromosome as a physical support. Retention of chronomere on the support is assisted with auxiliary heterochromatin’s proteins. The nucleotide sequence of the chronomere and its chromosomal original (the corresponding regulatory sequence of chromosomal DNA ) are identical. Therefore, chronomere sequences during the routine DNA sequencing remain unnoticed.

Chronomeres and printomeres are involved in maintaince of cellular differentiation, i.e. these perichromosomal organelles participate in the control of cell specificity. But in the brain’s neurons, chronomeres are responsible also for an another specific function: they are part of the life-long clock of a body. In neurons that differ in specificity, chronomeres respectively have distinct DNA sequences. Corresponding neurons, when they sequentially lose their chronomeres, are able to inform the body about its current physiological age: in this manner the neurons do change the properties of innervated body’s targets, i.e. body’s corresponding systems, organs, tissues and cells. That is why the numerous physiological and even anatomical characteristics gradually change in any person over time. Due to the loss of chronomeres by neurons, the body “knows” when, for example, it is the time to implement the puberty, when it is time for menopause or andropause, etc. Chronomere-related lifelong clock, or neuronal chronograph, performs its “ticking” already in the embryo, thus participating in the formation and then in the physiological maturation of the organism. But continuing to “tick” after maturation of his host, chronograph is eventually leading a host to the grave. The smaller the number of chronomeres left in the brain of an old person, the less, ceteris paribus, time is left to live for this human being.

Potential therapeutic uses of chronomeres: In the future, when it will be possible to regenerate chronomeres in an old brain (using as templates their chromosomal originals, which unlike chronomeres do not disappear from neurons), the doctors will be able to literally “twist off the clock back”, i.e. to directly rejuvenate the person. Another alternative is potentially not ruled out also – by slowing the losses of chronomeres it will be possible to get virtually a complete control over the pace of aging. To get such possibilities, it is necessary to perform enough hard work. The first crucial step is to find these amplificates. Only then the search for pharmacological and other means, which allow to control the process of aging, may become possible.

Linear DNA of chronomere has free ends, they are designated as the acromeres, to distinguish them from the telomeres that protect the free ends of the chromosomal DNA. Like telomeres, acromeres should protect its linear chronomeric DNA at its ends from exonucleases. By their nucleotide sequences, acromeres with high probability should have the vertebrate-like telomere repeats. In humans, the acromeres also may have TTAGGG repeats, but the number of such repeates in each acromere are probably much less compared with the long telomeres in the same neurons.

What should be done to identify chronomeres?

One can treat the samples of neuronal nuclear DNA with terminal transferase to add, for example, poly-T to all 3’ ends of DNA. Since the two DNA strands in a linear DNA molecule are antiparallel, the both poly-T tails in any sought-for amplificate (in a chronomere, as well as in a printomere) will be in an inverted orientation in regard to each other. The identification of such structures in the samples of neuronal chromosomes (using all proper controls to exclude occasional DNA breaks) will show the presence and even the locations of the sought-for chronomeres on the surface of chromosomal DNA in neurons.

Next steps – sequencing of identified chronomeres and preparing of catalogues of chronomeres for humans and laboratory animals. Following this, it will be possible to look for ways to regenerate chronomeres – restoring the aged neurons in vitro and then in the aged brains of animals. Also it will be possible to use some viral vectors armed with chronomeric sequences as an alternative way of neuronal rejuvenation.

A proved absence of the predicted perichromosomal amplificates in neurons would be a complete and unconditional refutation of the chronographic theory of aging. On the contrary, detection of chronomeres will be a pivotal event that will open the straight path to a future victory over numerous age-related pathologies and aging itself.

The key predictions of my former theory concerning cell aging, namely telomere theory, were: i) shortening of telomeres in dividing cells, ii) the existence of a special variant of DNA polymerase (a telomerase in current terminology), which should compensate telomere shortening, and iii) the prediction that this enzyme should be found in cancer cells and in sex cells. All these predictions of mine were confirmed – a quarter of a century later after their publication. The founder of Geron Corporation, Dr. M. West, has noted that this Corporation was organized taking into account the ideas of my telomere theory. The material on this subject can be found, for example, on these websites: http://www.michaelwest.org/Telomeres-as-the-Clock-of-Aging-and-Immortalization.htm ; https://web.archive.org/web/20161026194847/http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/2008/10/12/biotimes-quest-to-defeat-aging/ “Dr. West became so convinced of Olovnikov’s theory that he formed a company called Geron to investigate it further. As reported by Life Extension Magazine: “Forty million dollars later,” West recalls, “the gamble paid off.” West’s group had in fact produced Olovnikov’s mysterious enzyme…”

The aging of a body, though it is composed of cells, cannot be explained, however, only through the senescence of individual cells. Chronographic theory refers now to the higher levels of regulation, explaining both cellular aging and, more importantly, the organismal aging. It is not difficult to foresee that a new direction suggested by my chronographic theory of aging also will attract in the future the worldwide attention of scientific institutions and companies. Is it necessary to waste again another decades?

Alexey M. Olovnikov,

Moscow, olovnikov@gmail.com

Popular Longevity History and Fiction – in Hebrew

“25 עובדות מרתקות על נעורים, אריכות ימים וחיי נצח”

“25 עובדות מרתקות על נעורים, אריכות ימים וחיי נצח”

מאמר פופולארי על ההיסטוריה של רעיונות אודות הארכת חיים – שנועד לעורר עניין בחקר אריכות החיים כדי להמשיך ללימוד ומחקר מעמיקים יותר

Popular Life Extension history – Hebrew

יקום תרבות” – ספרות מדע בדיוני אודות הארכת חיים”

Loading…

Loading…

The pursuit of longevity is difficult – according to ancient Chinese alchemists

“Fu Lu Shou” – “the 3 Lucky Gods” of Chinese pantheon: Fu – Happiness (left), Lu – Prosperity (center), Shou – Longevity (right)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanxing_(deities)

http://www.longevityhistory.com/read-the-book-online/#_edn1221

http://life-extension-history.blogspot.co.il/2012/03/fu-lu-shou.html

Do they necessarily go together? Apparently not always, or even not often… In the pursuit of longevity science, prosperity and luck are often in short supply. Apparently, difficulties with funding and promotion of longevity research, were as old as longevity research itself, going back to the origins of Chinese Taoist alchemy. Here are some of the prominent protagonists voice their complaints from about 2000 years ago. Was this pursuit worth it? Hopefully. But let our ancient colleagues answer.

One of the earliest Chinese alchemists, Ko Hung (Ge Hong, 283-343 CE), wrote:

“I suffer from poverty and lack of resources and strength; I have met with much misfortune. There is nobody at all to whom I can turn for help. The lanes of travel being cut, the ingredients of the medicines are unobtainable. The result is that I have never been able to compound these medicines I am recommending. When I tell people today that I know how to make gold and silver, while I personally remain cold and hungry, how do I differ from the seller of medicine for lameness who is himself unable to walk? It is simply impossible to get people to believe you. Nevertheless, even though the situation may contain some unsatisfactory elements, it is not to be rejected in its entirety. Accordingly, I am carefully committing these things to writing because I wish to enable future lovers of the extraordinary and esteemers of truth, through reading my writings, to consummate their desires to investigate God [the Immortal Tao].”

(Alchemy, Medicine, Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei P’ien of Ko Hung (Pao-p’u tzu)” [Book of the] Master Who Embraces Simplicity], translated by James R. Ware, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge MA, 1966, Ch. 16 “The Yellow and the White,” p. 262.)

And the very first known author of Chinese alchemy, the man reputed for the invention of gun-powder, Wei Boyang (Wei Po-Yang), said c. 142 CE:

“I have abandoned the worldly route and forsaken my home to come here. I should be ashamed to return if I could not attain the hsien [immortality].”

(Lieh Hsien Ch’üan chuan, Complete Biographies of the Immortals, Tenney L. Davis, 1932, p. 214.)

“O, the sages of old!” Wei Boyang said “They held in their bosoms the elements of profundity and truth. … Their sympathy for those of posterity, who might have a liking for the attainment of the Tao (Way), led them to explain the writings of old with words and illustrations. They couched their ideas in the names of stones and in vague language so that only some branches, as it were, were in view and the roots were securely hidden. Those who had access to the discourses wasted their own lives over them. The same path of misery was followed by one generation after another with the same failure. If an official, his career was cut short; if a farmer, his farm was cluttered with weeds; if a merchant, his trade was abandoned; if an ambitious scholar, his family became destitute – in the vain attempt. These grieve me and have prompted the present writing. Although concise and simple, yet it embraces the essential points. The appropriate quantities [and processes] are put down for instruction together with confusing statements. However, the wise man will be able to profit by it by using his own judgement.”

(Wei Po-Yang, “Ts’an T’ung Ch’i” [“The akinness of the three”, i.e. of the alchemical processes, the Book of Changes, and the Taoist doctrines], Chapter LXII, pp. 257-258, in An ancient Chinese treatise on alchemy entitled Ts’an T’ung C’hi, Written by Wei Po-Yang about 142 A.D., Now Translated from the Chinese into English by Lu-Ch’iang Wu, With an Introduction and Notes by Tenney L. Davis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass., Isis, Vol. 18, No. 2, Oct. 1932, pp. 210-289.)